Tratturi – EN

It is impossible to talk about the economic, social and even political structure of the peoples of Abruzzo, from ancient times to a few decades ago, without referring to sheep breeding and therefore to a dense network of trade, including cultural exchanges, and the mobility of people, flocks, products and ideas. The peoples that a certain – now dated – historiography tended to consider “primitive” and entrenched in a centuries-old conservatism, always the same, appear to us today, in the light of the archaeological acquisitions of recent decades, as a living world, in constant evolution and change: this is demonstrated in a particularly clear way by funerary archaeology, which indicates that near long-distance roads, evidence of artefacts, structures and ritual forms of external origin or which testify to an osmosis with neighboring peoples multiply.

All this is understandable only by taking into account the existence of a dense road and communication network which was primarily responsible for the seasonal transit of animals and people through the so-called “transhumance“, the periodic migration of flocks along established routes; to a local phenomenon of transhumance called “vertical“, or “montification“, which took place in a limited area with the movement of animals from mountain to valley according to the seasons – and which had a significant impact on the characteristic elongated shape of the territory of our mountain municipalities -, contrasts with the much more substantial one of “horizontal” transhumance, through which, with movements lasting even many days, and with stays of months in the places of destination, flocks and shepherds reached from Abruzzo the Tavoliere delle Puglie in autumn to go back in spring. The aspect of the link is suggestive – particularly felt until after the Second World War – between these journeys and the cult of the Archangel Michael, whose annual celebrations coincided with the departure date of the migrations – 8 May and 29 September – and whose connection with the caves and springs suggest the overlap with the cult of the Italian demigod Hercules, protector of travel, trade, flocks and water.

Tutto ciò è comprensibile solo tenendo conto dell’esistenza di una fitta rete viaria e di comunicazione che era deputata innanzitutto al transito stagionale di animali e persone mediante la cosiddetta “transumanza“, la migrazione periodica delle greggi lungo percorsi stabiliti; ad un fenomeno locale di transumanza detta “verticale“, o “monticazione“, che si svolgeva in un comprensorio limitato con lo spostamento degli animali da monte a valle a seconda delle stagioni -e che ha tanto inciso sulla caratteristica forma allungata del territorio dei nostri comuni montani-, fa da contraltare quello, ben più consistente, della transumanza “orizzontale“, mediante la quale, con spostamenti anche della durata di molti giorni, e con permanenze di mesi nei luoghi di destinazione, greggi e pastori raggiungevano dall’Abruzzo il Tavoliere delle Puglie in autunno per tornare indietro in primavera. Suggestivo è l’aspetto del legame -particolarmente sentito fino al secondo dopoguerra- tra questi viaggi e il culto dell’Arcangelo Michele, le cui feste annuali coincidevano con la data di partenza delle migrazioni -8 maggio e 29 settembre- e la cui connessione con le grotte e le sorgenti suggerisce la sovrapposizione al culto del semidio italico Ercole, protettore appunto dei viaggi, dei commerci, delle greggi e delle acque.

Fonte: www.leviedeitratturi.com

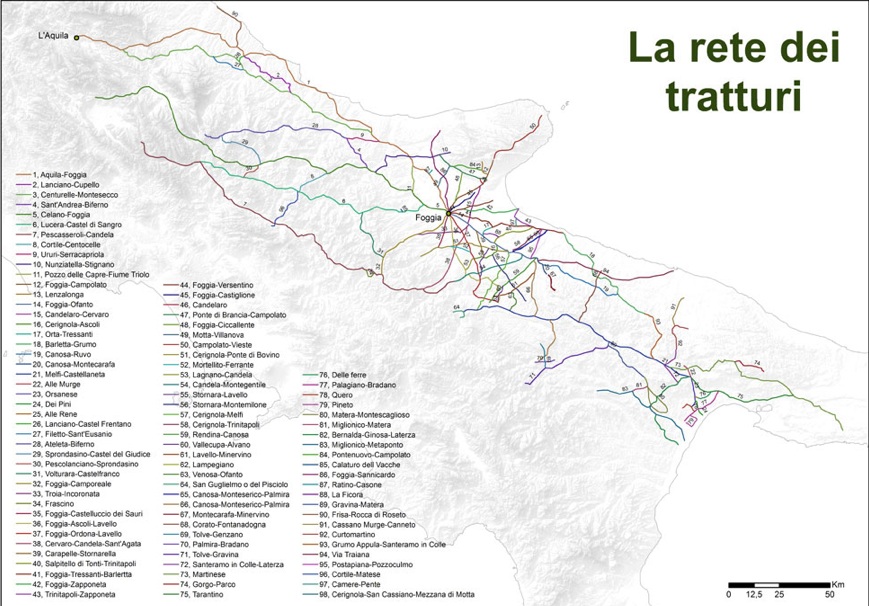

If there is a strongly conservative element in Abruzzo culture, which closely links antiquity and modernity, it is in the crystallization of the paths traveled by transhumant flocks, which follow the very ancient traditional itineraries over the centuries and millennia. The sheep track network, systematically organized in 1447 by King Alfonso I of Aragon, with a rigid codification of the routes and their widths measured in Neapolitan steps (111 steps was the width of the most important ones, first of all the Tratturo Magno which connected L’Aquila with Foggia), is roughly comparable, apart from a few variations, to a road system already in use for the seasonal movement of flocks and, consequently, also for commercial and cultural exchanges, of which we grasp the echoed in the material (FIG. 2), figurative (FIG. 3) and epigraphic archaeological documentation.

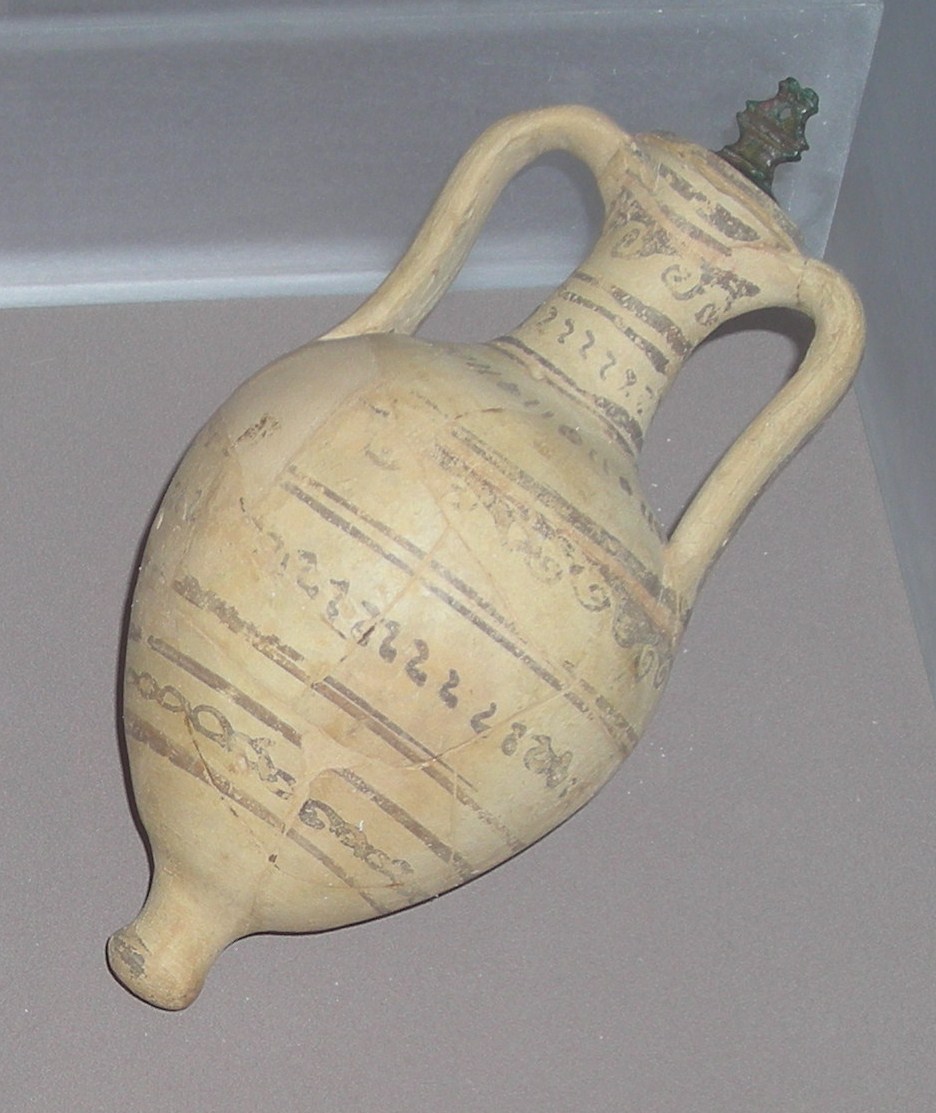

Anforetta canosina di III sec. a.C. (Corfinio, necropoli dell’Impianata, t. 4

Abbateggio, statua frammentaria di Ercole protettore dei viaggi

It is not uncommon, in fact, for the ” vie d’erba ” of Abruzzo to also follow the Roman consular routes, which, in turn, are set on roads and paths already in use since the Iron Age or even from a previous period.

The current legislation for the protection of the sheep track network, therefore, has a dual aspect. On the one hand, the bodies in charge, Sabap first and foremost, aim to preserve the integrity of the materiality of the routes, where not yet compromised by the continuous – and often devastating – human interference of the last fifty years, which in many places has irreversibly modified the layout and perception of the territory; in this sense, the ministerial decrees of 1980 and 1983, which subject sheep tracks to the regime of declared cultural heritage, represent a fixed point to which the ABAP Superintendence for the provinces of Chieti and Pescara constantly refers in its daily work. On the other hand, the very recent inclusion of transhumance among the intangible heritage of UNESCO (December 2019) catalyzes attention towards everything that the existence of such a complex tractor road network in our territory presupposes and implies: a very dense network of goods, people, models, objects, concepts, cults and forms of thought, without which a real knowledge – and consequent valorisation – of the peculiar culture of our region would be precluded.

- Aree Tematiche

- Archaeological Heritage

- Patrimonio Storico – Artistico

- Architectural Heritage

- Demoethnoanthropological heritage

- Tratturi – EN

- Education and Research

- Historical – Artistic Heritage

- Landscape

- Patrimonio Archeologico

- Patrimonio Architettonico

- Patrimonio Demoetnoantropologico

- Paesaggio

- Tratturi

- Educazione e Ricerca